-

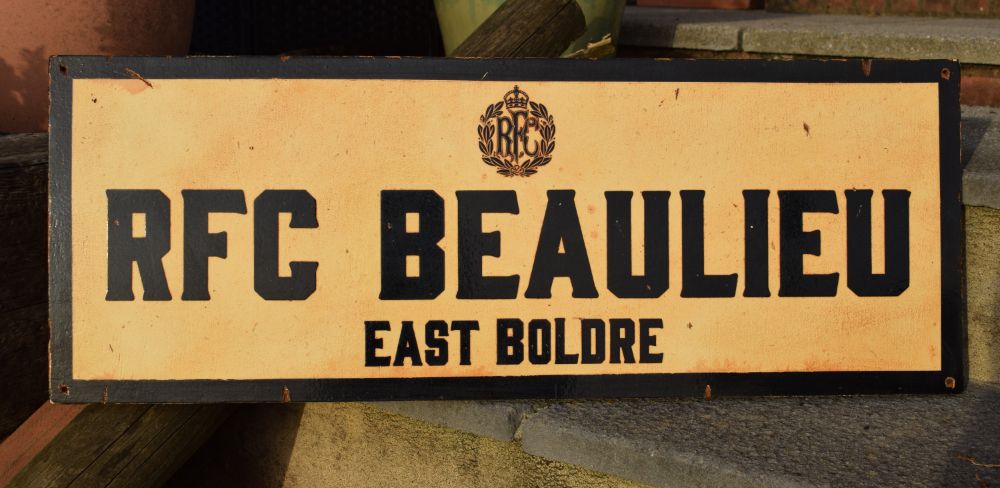

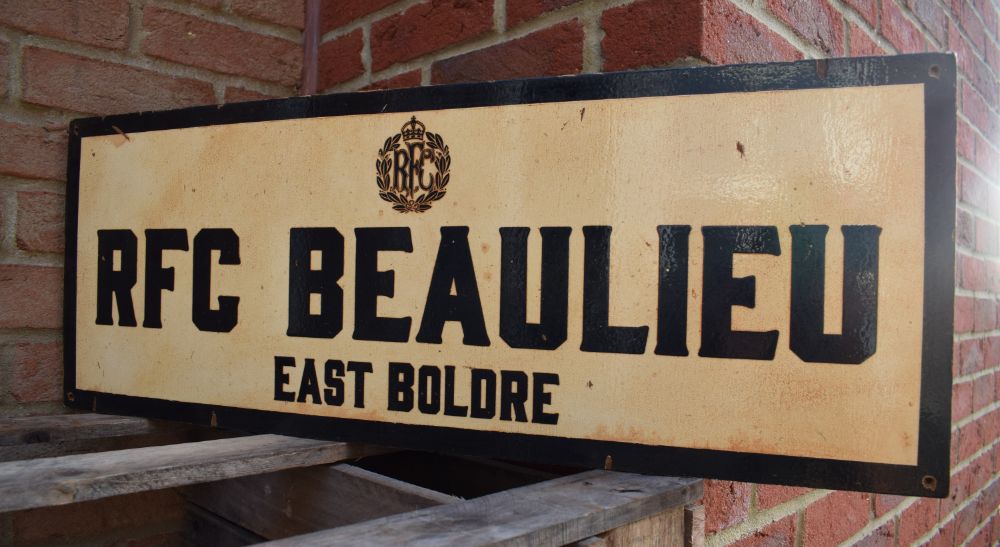

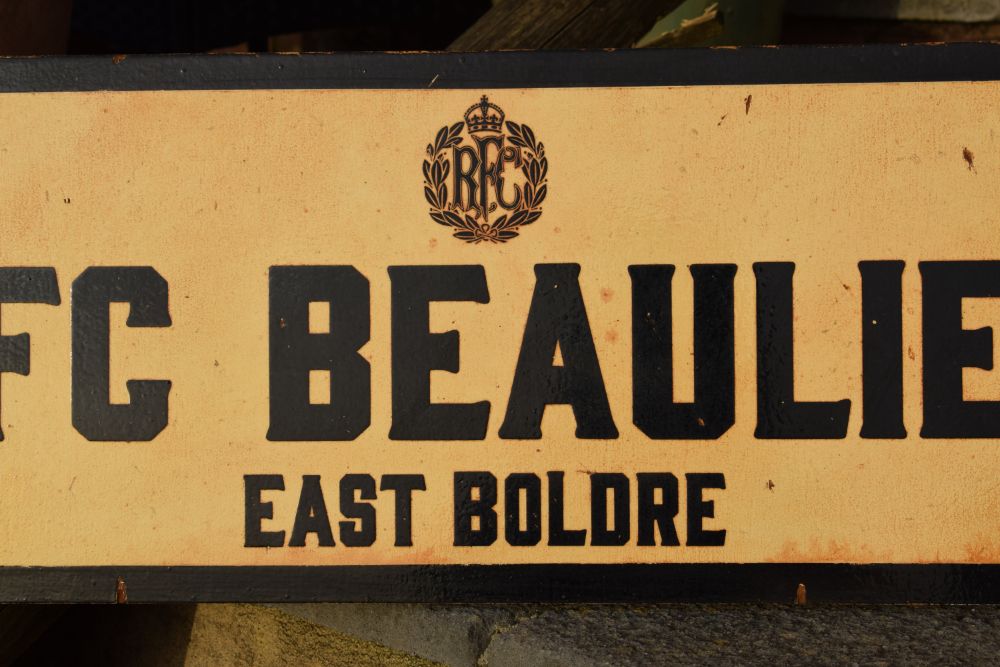

Royal Flying Corps - Beaulieu

- Wooden sign. 750mm x 208mm

- £79.95

RFC Beaulieu.

Flat areas of land in the New Forest region were highly suitable for creating airfields, especially as they were situated near the south coast, making them a useful base for aircraft operating over Europe. During World War One, a Royal Flying Corps training airfield – RFC Beaulieu – existed at East Boldre. At the beginning of World War I, flying machines were very much a new technology with limited perceived military potential - indeed, powered flight was just eleven years old and the British air force comprised a mere thirty-three machines flying under the auspices of the Royal Flying Corps.

Aircraft such as the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2, a single-engine two-seat biplane, were used initially for reconnaissance and artillery observation behind enemy lines rather than for combat. Utilising large, unwieldy, primitive cameras, observers leant over the side of the aircraft to take photographs of the battlefields below to enable artillery fire to be more accurately directed at enemy targets.

Air crews were initially unarmed although, as enemy aircraft were often engaged on similar missions, pilots would take along pistols and rifles to fire if the need arose. Grenades and small bombs also began to be carried in the cockpit and were dropped over the side of the aircraft onto the enemy below.

But as the importance of aerial observation grew, the need to take aggressive action against enemy aircraft became clear and so did a requirement to develop defensive capabilities. Specially adapted Lewis machine guns, mounted or fired from the shoulder, became the weapon of choice, initially used by the observer from the rear of the aircraft so as to avoid damaging the whirling propeller blades.

By 1915, however, forward facing machine guns were being fitted onto aircraft, eventually cleverly synchronised to shoot through the propeller blades without causing damage. And by 1916 and 1917, fewer lone fighters cruised the skies and instead larger formations of aircraft flew together, with individuals breaking away to engage in 'dog fights'.

New aircraft were introduced into service, aircraft such as the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 (from March 1917) and the later improved S.E.5a, fast, nimble single seater fighters that, although still wooden framed and fabric covered, have since been described as the 'Spitfires of World War One'.

Reflecting air power's increasing importance to the war effort, on 1st April, 1918 the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service were amalgamated to form the Royal Air Force. Fighters by then were being used at low levels to support ground troops, whilst specialist bombers had been developed that could fly for up to eight hours at a top speed of ninety-seven miles per hour (156 km per hour) while carrying one ton of bombs - the bombers, of course, were not very manoeuvrable and needed protection from accompanying fighter aircraft.

So, during a little over four short years, the use of aircraft had evolved from flying simple but extremely dangerous reconnaissance missions to being important weapons of war with a hugely significant military role.

During the Second World War there were 12 airfields in the New Forest (including 9 built during the war). Opened on 8 August 1942, Beaulieu became used as the base for a variety of aircraft (bomber and fighter squandrons) needed to support rapidly developing theatres of war – initially by the Royal Air Force (2nd Tactical Air Force), then later US Army Air Forces (USAAF) in 1944.

On D-Day, P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers of 365th Fighter Group (known as ‘The Hellhawks’) took off from RAF Beaulieu to divebomb and attack German gun positions and communication hubs in Normandy in preparation for Operation Overlord, to prevent the Germans halting the advance of the troops landing on the D-Day beaches.

On 7 September 1944 the airfield was transferred back to the RAF, and later in January 1945, control was passed to Flying Training Command.

Throughout the war, agents and resistance fighters from the Special Operations Executive were flown into occupied Europe – as some of their training was performed locally around Beaulieu, they were frequently transported by planes from Beaulieu airfield to Europe. Around 9 of the larger houses around Beaulieu were used by the S.O.E. as a ‘finishing school’ to give the agents a chance to practise their skills before being deployed overseas.

After the war, RAF Beaulieu was used for experimental flying and as a stand-by airfiled, before it was closed in 1959.